- Messages

- 18

- Reaction score

- 45

- Points

- 1,015

The European Hamster

The European hamster is the largest, and most endangered, species of hamster. With their charming and photogenic faces, they have captured the hearts of many, but that wasn’t always the case. The following series of posts will give an overview of their physical appearance, behaviour and living habits. They will also cover their relationship with humans, their critically endangered status, and the steps people are taking to protect them. Finally, I will share an account from the early 20th century of European hamsters kept as pets.

Above: A European hamster, in his characteristic pose, showing off his striking black belly. Source: Shutterstock.

European hamsters are native to grassland and steppe regions ranging from Belgium to as far east as the western edge of Mongolia. They may also be found in green pockets of urban areas. In particular, there is a large population in Vienna Central Cemetery in Austria.

The European hamster is a handsome animal. They usually have rust-brown fur with white flashes on the cheeks and sides of the upper body, white feet, and a striking black belly, though there is some variety in their coloration. Rarely, an individual might even be entirely white or entirely black.

They are very similar in body structure to the Syrian hamster, but significantly larger. European hamsters are approximately the size of a guinea pig or a grey squirrel, being about 24cm long and typically weighing 350-450g. The females tend to be slightly smaller and lighter than the males. Their ears, one of their most endearing features, are also proportionally larger than Syrians’ ears.

Above: Fully grown male Syrian and European hamsters. Source: Clinical Anatomy of the European Hamster.

Like other hamsters, they have cheek pouches which they use to carry large amounts of grain and other food for hoarding, and like Syrian and Chinese hamsters, they have scent glands on their hips which they use to mark their territory.

The zoologist Alfred Brehm reported in his Tierleben (a famous German encylopaedia of animals) that the hamsters have good eyesight, at least equally as good as their other senses. This sets them apart from most other hamster species which are considered to have poor eyesight. The hamsters are often pictured standing upright on their hind legs, looking alertly at something in the distance, or as Brehm (who in the course of this post you may detect has a strong dislike for the European hamster) prefers to describe, “glar[ing] at the object of its resentment, evidently quite ready for an opportunity of rushing at it and using its teeth on it.”

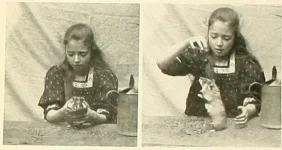

European hamsters are well-known for being naturally rather aggressive (to their own species and other species), which is one reason why many don’t consider them to make good pets, although there are accounts of them being tamed in a captive environment.

Brehm paints a fearsome picture of the hamsters, describing them as “ugly, sulky, and irritable… also very pugnacious.” Brehm’s picture may perhaps be exaggerated, but on the latter point, at least, he was correct. European hamsters will respond furiously to any actual or perceived threat, and will fight back tenaciously when attacked, even by much larger animals. Brehm reports that they will even attack horses and people unprovoked. BBC Wildlife more sympathetically describes them as “bolshy”.

European hamsters seem to be particularly vocal and are often described as growling when surprised or afraid. They will also grind and chatter their teeth as an aggressive gesture. They can jump a metre, or perhaps higher, despite their stocky build. You can see a brief clip of two hamsters fighting here.

Last edited by a moderator: